---

title: "Numbering Numbers, Part 2: Ordering Obliquely"

description: |

How do we count an infinitude of numbers?

format:

html:

html-math-method: katex

date: "2023-12-31"

date-modified: "2025-07-26"

categories:

- algebra

- question-mark function

- haskell

---

```{haskell}

--| echo: false

:l Diagonal

:l Previous

import Data.Tree

import Data.Profunctor

import IHaskell.Display.Blaze

import Text.Blaze.Colonnade

import qualified Text.Blaze.Html4.Strict as Html

import qualified Text.Blaze.Html4.Strict.Attributes as Attr

import Diagonal hiding (displayDiagTable)

import Previous

redSpan = (Html.span Html.! Attr.style (Html.toValue "color: red")) . Html.string

greenSpan = (Html.span Html.! Attr.style (Html.toValue "color: green")) . Html.string

displayDiagTable ps n = ect $ rmap style diagBox' where

diagBox' = diagBox n

ect = encodeCellTable (Attr.class_ $ Html.toValue "")

-- style the diagonal as red and rows numbered as `ps` as green

style = either (stringCell . show) htmlCell . displayRows (redSpan . show) (map (, greenSpan . show) ps)

```

This post assumes you have read the [previous one](./1), which discusses the creation of sequences

containing every integer, every binary fraction, and in fact, every fraction.

From the fractions, we also could enumerate quadratic irrational numbers using the *question-mark function*.

Other Irrationals

-----------------

Because rationals -- and even some irrationals -- can be enumerated, we might imagine

that it would be nice to enumerate *all* irrational numbers.

Unfortunately, we're not very lucky this time.

Let's start by making what we mean by "number" more direct.

We've already been exposed to infinite expansions, like 1/3 in binary (and conveniently, also decimal).

In discussing the question mark function, I mentioned the utility of repeating expansions as a means of

accessing quadratic rationals in the Stern-Brocot tree.

A general sequence need not repeat, so we choose to treat these extra "infinite expansions" as numbers.

Proving that a rational number must have a repeating expansion is difficult, but if we accept this premise,

then the new non-repeating expansions are our irrationals.

For example, $2 - \varphi \approx 0.381966...$, which we encountered last time, is such a number.

Doing this introduces a number of headaches, the least of which is attempting to do arithmetic with such quantities.

However, we're only concerned with the contents of these sequences to show why we can't list out all irrationals.

### Diagonalization

We can narrow our focus to the interval between 0 and 1, since the numbers outside this interval

are their reciprocals.

Now (if we agree to use base ten), "all numbers between 0 and 1" as we've defined them begin with "0.",

followed by an infinite sequence of digits 0-9.

Suppose that we have an enumeration of every infinite sequence on this list -- no sequence is left out.

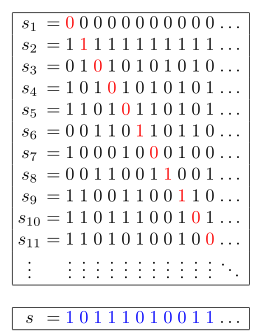

[Cantor's diagonal argument](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cantor%27s_diagonal_argument) shows that

a new sequence can be found by taking the sequence on the diagonal

and changing each individual digit to another one.

The new sequence differs in at least one place from every element on the list, so it cannot be on the list,

showing that such an enumeration cannot exist.

This is illustrated for binary sequences in this diagram:

It's fairly common to show this argument without much further elaboration,

but there are a few problems with doing so:

- We're using infinite sequences of digits, not numbers

- Equality between sequences is defined by having all elements coincide

- We assume we have an enumeration of sequences to which the argument applies.

The contents of the enumeration are a mystery.

- We have no idea where the rational numbers are, or if we'd construct one

by applying the diagonal argument

### Equality

The purpose of the diagonal argument is to produce a new sequence which was not previously enumerated.

The sequence is different in all positions, but what we actually want is equality with respect to the base.

In base ten, we have the peculiar identity that [$0.\overline{9} = 1$](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/0.999...).

This means that if the diagonal argument (applied to base ten sequences) constructs a new sequence with the digit 9 repeating forever,

it might be equivalent to a sequence which was already in the list:

```{haskell}

--| code-fold: true

--| classes: plain

--| fig-cap: A case in which the diagonal argument could construct a number already on the list.

diagData = rowsOmega [

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6],

[9, 2, 4, 8, 3, 7],

[2, 2, 8, 2, 2, 2],

[2, 3, 9, 3, 9, 9],

[9, 4, 9, 4, 9, 4],

[8, 1, 2, 5, 7, 9]

]

[2, 3, 9, 4, 0, 0]

displayDiagTable [Just Omega, Just $ RN 3] 5 diagData

```

In the above table, sequence 3 is assumed to continue with 9's forever.

The new sequence ω comes from taking the red digits along the diagonal and mapping each digit

to the next one (mod ten).

In the enumeration given, the diagonal continues with 9's forever, so we end up with 0's forever in ω.

### Picking a Sequence and Ensuring Rationals

"No problem, just pick another enumeration," you might say.

Indeed, the example given relies on a simple function applied on the diagonal and an enumeration

to which it is particularly ill-suited.

Instead, let's focus on something we *can* do.

Instead of assuming we have all irrational numbers listed out already, let's start smaller.

As of last post, we already have several ways to enumerate all rational numbers between 0 and 1.

If we take this enumeration, convert rational numbers to their expansions in a base, and apply the diagonal argument,

the resulting quantity *should* be an irrational number.

For convenience, we'll use the binary expansions of rationals as our sequences.

That way, to get a unique sequence on the diagonal, we only have to worry

about changing "0"s to "1"s (and vice versa).

Since we have less flexibility in our digits, it also relieves us from some of the responsibility

of finding a "good" function, like in the decimal case.

However, it's still possible the argument constructs a number already equal to something on the list.

Into Silicon

------------

Before going any further, let's convert the diagonal argument into a function.

We want to, given an enumeration of binary sequences, produce a new sequence not on the list.

This can be implemented in Haskell fairly easily:

```{haskell}

diagonalize :: [[Int]] -> [Int]

-- pair each sequence with its index

diagonalize xs = let sequences = zip [0..] xs in

-- read out the red diagonal

let diagonal = map (\(n, s_n) -> s_n !! n) sequences in

-- map 0 to 1 and vice versa

map (1 -) diagonal

-- or in point-free form

-- diagonalize = map (\(x,y) -> 1 - (y !! x)) . zip [0..]

```

Nothing about this function is specific to "binary sequences", since `Int` contains values

other than `1` and `0`.

It's just more intuitive to work with them instead of "`True`" and "`False`"

(since `Bool` actually does have 2 values).

You can replace `(1 -)` with `not` to get a similar function for the type `Bool`.

We also need a function to get a rational number's binary expansion.

This is simple if you recall how to do long division.

We try to divide the numerator by the denominator, "emit" the quotient as part of the result list,

then continue with the remainder (and the denominator is unchanged).

It's not *quite* that simple, since we also need to "bring down" more zeroes.

In binary, we can add more zeroes to an expansion by just multiplying by 2.

```{haskell}

--| layout-ncol: 2

binDiv :: Int -> Int -> [Int]

-- Divide n by d; q becomes part of the result list

-- The rest of the list comes from doubling the remainder and keeping d fixed

binDiv n d = let (q,r) = n `divMod` d in q:binDiv (2*r) d

x = take 10 $ binDiv 1 3

y = take 10 $ binDiv 1 5

putStrLn $ "x = 1 / 3 = 0." ++ (tail x >>= show) ++ "..."

putStrLn $ "y = 1 / 5 = 0." ++ (tail y >>= show) ++ "..."

```

This function gives us the leading 0 (actually the integer part of the quotient of `n` by `d`),

but we can peel it off by applying `tail`.

Since we intend to interpret these sequences as binary numbers, we might as well also

convert this into a form we recognize as a number.

All we need to do is take a weighted sum of each sequence by its binary place value.

```{haskell}

fromBinSeq :: Int -> [Int] -> Double

-- Construct a list of place values starting with 1/2

fromBinSeq p = let placeValues = (tail $ iterate (/2) 1) in

-- Convert the sequence to a type that can multiply with

-- the place values, then weight, truncate, and sum.

sum . take p . zipWith (*) placeValues . map fromIntegral

oneFifth = fromBinSeq 64 $ tail $ binDiv 1 5

print oneFifth

```

The precision `p` here is mostly useless, since we intend to take this to as far as doubles will go.

`p` = 100 will do for most sequences, since it's rare that we'll encounter more than a few zeroes

at the beginning of a sequence.

Some Enumerations

-----------------

Now, for the sake of argument, let's look at an enumeration that fails.

Using the tree of binary fractions from the last post, we use a breadth-first search to create a list of terminating binary expansions.

```{haskell}

--| classes: plain

-- Extract the left subtree (i.e., the first child subtree)

badDiag diagonalize = let (Node _ (tree:__)) = binFracTree in

diagonalize $ map (tail . uncurry binDiv) $ bfs tree

buildDiagTable n = (rowsOmega . take n) <*> diagonalize

-- TODO: show fraction

displayDiagTable [] 7 $ badDiag (buildDiagTable 8)

```

Computing the diagonal sequence, it quickly becomes apparent that we're going

to keep getting "0"s along the diagonal.

This is because we're effectively just counting in binary some number of digits to the right.

The length of a binary expansion grows logarithmically rather than linearly; in other words,

we can't count fast enough by just adding 1 (or adding any number, really).

Even worse than this, we get a sequence which is equal to sequence 1 as a binary expansion.

We can't even rely on the diagonal argument to give us a new number that *isn't* equal

to a binary fraction.

### Stern-Brocot Diagonal

The Stern-Brocot tree contains more than just binary fractions, so we're bound to encounter more than

"0" forever when running along the diagonal.

Again, looking at the left subtree, we can read off fractions between 0 and 1.

We end up with the following enumeration:

```{haskell}

--| classes: plain

-- Extract the left subtree (i.e., the first child subtree)

sbDiag diagonalize = let (Node _ (tree:__)) = sternBrocot in

diagonalize $ map (tail . uncurry binDiv) $ bfs tree

-- TODO: show fraction

displayDiagTable [] 7 $ sbDiag (buildDiagTable 8)

```

When expressed as a decimal, the new sequence corresponds to the value 0.12059395276... .

Dually, its continued fraction expansion begins \[0; 8,3,2,2,1,2,12, ...\].

While the number is (almost) certainly irrational, I have no idea whether it is algebraic or transcendental.

### Pairs, without repeats

We have a second, similar enumeration given by `allRationalsMap` in the previous post.

We'll need to filter out the numbers greater than 1 from this sequence, but that's not too difficult

since we're already filtering out repeats.

```{haskell}

--| classes: plain

-- Only focus on the rationals whose denominator is bigger

arDiag diagonalize = let rationals01 = filter (uncurry (<)) allRationals in

diagonalize $ map (tail . uncurry binDiv) rationals01

-- TODO: show fraction

displayDiagTable [] 7 $ arDiag (buildDiagTable 8)

```

This new sequence has a decimal expansion equivalent to 0.24005574958...

(continued fraction expansion begins \[0; 4, 6, 28, 1, 1, 5, 1, ...\]).

Again, this is probably irrational, since WolframAlpha has no idea on whether a closed form exists.

The Diagonal Transform

----------------------

Why stop with just one?

This new number can just be tacked onto the beginning of the list.

Then, we re-apply the diagonal argument to obtain a new number.

And so on ad infinitum.

```python

#| echo: false

#| classes: plain

diag2 = lambda d, yss: [

[

d.get(i - j, lambda x: x)(y)

for j, y in enumerate(ys)

]

for i, ys in enumerate(yss)

]

Markdown(tabulate(

[["...", "", *(["..."]*9)]]

+ zipconcat(

[

[green("-2"), ""],

[red("-1"), ""],

[0, "1/2"],

[1, "1/3"],

[2, "2/3"],

[3, "1/4"],

[4, "2/5"],

[5, "3/5"],

[6, "3/4"],

[7, "1/5"],

["...", "..."],

],

diag2(

{

1: green,

2: red,

},

[

[1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1],

[0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0],

[1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1],

[1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0],

[1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1],

[1, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1],

["...", "...", "...", "...", "...", "...", "...", "..."],

]

),

[["..."]]*12,

),

headers=["*n*", "Number", *range(8), "..."],

))

```

Using the Stern-Brocot enumeration ~~because I like it better~~

```{haskell}

transform :: [[Int]] -> [[Int]]

-- Emit the new diagonal sequence, then recurse with the new sequence

-- prepended to the original enumeration

transform xs = let ds = diagonalize xs in ds:transform (ds:xs)

sbDiagSeq = let (Node _ (tree:__)) = sternBrocot in

transform $ map (tail . uncurry binDiv) $ bfs tree

mapM_ print $ take 10 $ map (fromBinSeq 100) sbDiagSeq

```

Does this list out "all" irrational numbers? Not even close.

In fact, this just gives us a bijection between the original enumeration and a new one containing our irrationals.

The new numbers we get depend heavily on the order of the original sequence.

This is obvious just by looking at the first entry produced by our two good enumerations.

Perhaps if we permuted the enumeration of rationals in all possible ways, we would end up listing

all irrational numbers, but we'd also run through

[all ways of ordering the natural numbers](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baire_space_%28set_theory%29).

The fact that "bad" enumerations exist tells us that it's not even guaranteed that we don't collide

with any rationals.

I conjecture that the good enumerations won't do so, since we shouldn't ever encounter

an infinite sequence of "0"s, and a sequence should eventually differ

in at least one position from one already listed.

### Almost Involution

Since the function has the same input and output type, you may wonder what happens when

it's applied multiple times.

Perhaps you assume that, since `\x -> 1 - x` swaps 0 and 1, we'll get the original sequence back again.

Alas, experimentation proves us wrong.

```{haskell}

--| layout-ncol: 2

sbDiagSeq2 = transform sbDiagSeq

mapM_ print $ take 10 $ map (fromBinSeq 100) sbDiagSeq2

-- Guesses

mapM_ putStrLn [ "1/2", "1/3", "11/12", "1/8", "57/80", "23/80",

"55/64", "3/40", "???, possibly 613/896", "249/512" ]

```

The fraction forms of the above numbers are my best guesses.

Either way, it only matches for the first two terms before going off the rails.

Even stranger than this distorted reflection is the fact that going through the mirror again doesn't take us anywhere new

```{haskell}

sbDiagSeq3 = transform sbDiagSeq2

squaresAgree n xs ys = let takeSquare zs = take n $ map (take n) zs in

takeSquare xs == takeSquare ys

mapM_ print $ take 10 $ map (fromBinSeq 100) sbDiagSeq3

-- First and third iterates agree

print $ squaresAgree 100 sbDiagSeq sbDiagSeq3

```

In other words, applying the transform thrice is the same as applying the transform once.

Not that this has been shown rigorously in the least -- it's only been tested in a 100x100 square.

Regardless, this semi-involutory behavior is strange and nontrivial.

And it's not limited to this enumeration.

For example, the filtered `allRationalsMap` iterations shows:

```{haskell}

--| layout: [[1, 1], [1]]

arDiagSeq = let rationals01 = filter (uncurry (<)) allRationals in

transform $ map (tail . uncurry binDiv) rationals01

-- What goes in isn't what comes out

mapM_ print $ take 10 $ map (fromBinSeq 100) $ transform arDiagSeq

-- Guesses

mapM_ putStrLn ["1/2", "1/3", "3/4", "1/6", "7/10", "5/12", "139/160", "13/128", "???, possibly 949/1792", "633/1280"]

-- First and third iterates agree

print $ squaresAgree 100 arDiagSeq (transform $ transform arDiagSeq)

```

Meanwhile, the bad enumeration just gives more binary fractions, but it still doesn't mean

double-transforming returns the original diagonal.

```{haskell}

--| layout: [[1, 1], [1, 1], [1]]

bfDiagSeq = let (Node _ (tree:__)) = binFracTree in

transform $ map (tail . uncurry binDiv) $ bfs tree

(putStrLn "First diagonal transform: " >>) $

mapM_ print $ take 10 $ map (fromBinSeq 100) bfDiagSeq

-- Guesses

mapM_ putStrLn ["Guesses", "1/4", "1/1", "1/2", "5/8", "1/16", "25/32", "25/64", "81/128", "49/256", "417/512"]

-- What goes in isn't what comes out

(putStrLn "Second diagonal transform: " >>) $

mapM_ print $ take 10 $ map (fromBinSeq 100) $ transform bfDiagSeq

-- Guesses

mapM_ putStrLn ["Guesses", "1/2", "1/4", "3/4", "1/8", "11/16", "15/32", "55/64", "15/128", "143/256", "223/512"]

-- First and third iterates agree

print $ squaresAgree 100 bfDiagSeq (transform $ transform bfDiagSeq)

```

What does it mean that the initial enumeration comes back as a completely different one?

Since the new one is "stable" with respect to applying the diagonal transform twice,

are the results somehow preferable or significant?

Closing

-------

These questions, and others I have about the products of this process, I unfortunately have no answer for.

I was mostly troubled by how rare it is to find people applying the diagonal argument

to something to anything other than random sequences.

Random sequences, either by choice or by algorithm (if you can even call them random at that point),

are really only good to show *how* to apply the diagonal argument.

Without knowing *what* the argument is applied to, it's useless for constructive arguments.

It also still remains to be proven that your new sequences are sufficient for the purpose

(since I've only shown a case in which it fails).

(Recycled) diagrams made in Geogebra.